Balcarka Cave - history

ARCHAEOLOGY AND PALEONTOLOGY

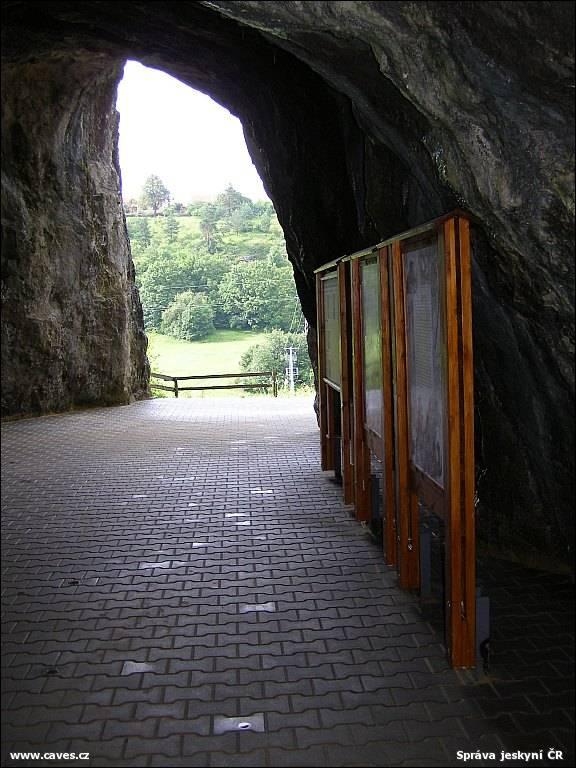

The entrance portal of the Balcarka Cave was the subject of paleontological and archaeological research studies as early as in the 19th century. After exploratory excavations of Dr. Jindřich Wankel, systematic research was performed here by Jan Knies in 1898–1904.

He managed to discover rich traces of human activity in the Upper Palaeolithic – 6 fireplaces and many stone and bone tools. In sediments from the cave portal, even thousands of skeletons, predominantly of little animals that lived here at the end of the last ice age – over 30,000 skeletons of voles, 8,000 of lemmings, 1,500 of pikas, 600 of shrews, 300 of hamsters, 1,200 of willow grouses, 400 of rock ptarmigans – survived. There have also been archaeological and paleontological discoveries in other places from the surroundings of the Balcar’s Rock – even a human tooth from the Žižkůvka Cave. It was, however, lost during World War II and since there is no other material available, its age cannot be determined precisely.

HISTORY, DISCOVERING AND OPENING UP OF THE BALCARKA CAVE

"In the Balcarka Cave, there once lived wild women. They wore a white cap on their heads, a green jacket on their bodies and a long white skirt. Once Balcar was ploughing his field that lay in front of the rock. The nymphs came to him and asked him to fix their broken shovel, saying: Balcar, you old fella, can thou fix this shovel of ours? Balcar did as they wished. Then, having repaired the shovel and brought it back, he got a pie and the pie was said to be never finished, indeed, keeping its freshness at all times. Balcar accepted the gift and stored the pie in his pantry. Devouring that very good pie, they always left a bit of it in the pantry, seeing the pie had been restored in the morning. One day, though, Balcar ate the whole pie to see what would happen. In the morning, a cowpat was found in the pantry instead of the pie. This punished Balcar for his curiosity."

Up until the 19th century, Balcar’s Rock with its mysterious opening had the respect of local inhabitants. There are many superstitions and legends connected with this cave. It became a subject of interest as recently as in the second part of the 19th century. In the 1920s, Josef Šamalík, a local resident, farmer and also deputy started his activities on Balcar’s Rock and in the surroundings. He walked on the ground, a divining rod in his hands, and searched for ways into the supposed caves. And on 16th June 1923 he finally succeeded and got into the underground spaces. This is how the discoverer describes his first impressions:

“The cave is not big, but beautiful. There are two chapels in the front part and in one of them there is even an altar of stones. The chapels are decorated in white, with travestines and stalactites and stalagmites of various shapes. The right part of the cave is decorated with many white stalactites and stalagmites, curiously formed. The space blocked with boulders and earth was freed, another entrance was broken through and at the same time the small cave was made accessible from the upper part as well. The whole interior of the cave, i.e. not only the upper and side walls, but also the bottom, is white and decorated with many stalactites and stalagmites. There is one remarkable stalagmite among them called Handžár (Yataghan), curved like a Turkish sword. Opposite it there is a conical stalagmite. The workers gave the cave my name. However, I gave it the name Popeluška (Cinderella)...”

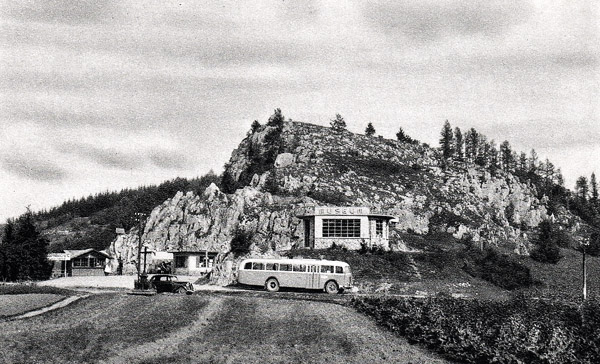

Josef Šamalík continued with breakthrough works in Popeluška, however without success. That winter he noticed melted snow in the small doline on the top of Balcar’s Rock. Together with helpers he gradually loosened the filling and he succeeded in getting into other free spaces of the Balcarka Cave. This event was dated by him as 22nd February 1924.

In the following months Josef Šamalík made his way into the next spaces – gradually he discovered Wilsonovy rotundy (Wilson's Rotundas), Dóm zkázy (Destruction Chamber) and the largest one – Fochův dóm (Foch's Chamber). Then, he started opening the cave to the public. In spite of financial problems and thanks to the help of the Moravský kras company, this cave was opened on Easter Sunday in 1925 and “passed on to the general public”.